by Dan Friesen

* from a presentation of 10 Cultural Lessons given in 2015

The importance of style in the Romance countries – Spain, France, Italy

One of the early lessons I learned about cultural differences came in the Romance countries of Europe: Spain, France, and Italy. This lesson involved differences between European appreciation of style and form and American priorities of pragmatism and practicality.

My wife will tell you that I have never been a clothes horse, and any of the WAI guide team who’ve traveled with me will attest to the fact that I see food primarily as biological fuel. It’s not that my taste buds are seared; I’m simply very practical when it comes to prioritizing time and resources, especially while traveling.

Clothing is functional and food is fuel. Perhaps such pragmatic values are an outgrowth of our parents and grandparents enduring the Great Depression and World War II. Function trumps style. Perhaps genetics plays a part; my northern Europe Mennonite farmer roots instinctively prioritize practicality and productivity. Whatever the cause, the differences in mentality are significant.

Clothing as functional?

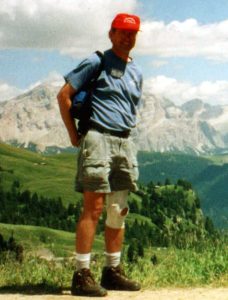

In the early years of WAI, the walker’s uniform was a pair of shorts, a t-shirt, and a pair of running shoes (the photo above was taken after I graduated to hiking boots). As I traveled Europe planning tours and guiding in the 1990s, I deviated very little from this uniform. Not the most observant male of the species, it took a few years of crisscrossing Europe to realize that European men don’t generally show their legs unless they are working out. Wearing shorts in an urban setting is especially counter-cultural.

In 1994 or 1995, I was alone in Seville setting up a new series of walks, wandering the charming cobblestone lanes of this delightful southern Spain city with a map and clipboard, wearing my “uniform”.

While standing at a corner in the pedestrianized zone making notes on my map, I noticed a trio of young, sweater-clad schoolgirls, probably about 11 years old, watching me and whispering. I made eye-contact and one of them hugged herself, imitating a shiver, and asked “frio?”—as if to say, “aren’t you cold?”.

Being of northern European descent, I was not cold on that lovely 70-degree day. But certainly, I stood out like a sore thumb with my ultra-casual exercise attire in the middle of the staid, traditional historic district of Seville.

As I spent more time in Spain, France, then Italy, the so-called Romance nations (speaking languages evolved from Roman Latin), I began to appreciate the visual impact of style in clothing. The cut of the jeans; a slightly fitted vest or jacket; a pair of leather shoes; and a scarf. A scarf seems the universal statement of style, for both men and women. And these things make a difference, even to a less than sensitive, old-school American male. Style in clothing impacts feeling, which in turn impacts human connection and relationship.

Food as Fuel?

In the fall of the year 2000, I finished a tour through Central Europe, said farewell to my group at the Amsterdam airport, and hopped on a train to zip south along the Rhine River to the Freiburg area of southern Germany.

My German friends, Willi and Yvette Neuhof, had offered to help make contact with leaders of the French walking federation. The objective was to achieve authorization of our walks in France for the volkssport booklet stamps many of our walkers covet.

Willi and Yvette met me at the train station and took me to dinner in a small Gasthaus inn typical of this part of Europe. The ambiance was welcoming…warm tones of wood paneling and furnishings, just the right amount of light, and a delicious meal accompanied by quality beer. Though a self-confessed non-foodie, over 20 years later I still recall that evening with a sensation of warmth and conviviality—good food and drink in a cozy, hospitable setting with friendly warm conversation. Germanic cultures have a term reserved just for this ambiance–“gemütlichkeit”. It was a foretaste of my first truly French meal the next day.

In the morning, Willi and I headed across the border into France in style in his Mercedes. Our destination was a small town in the Alsace region of northeast France.

It was late October. The countryside had lost its appealing autumn palette. The town in which we arrived was non-descript. The restaurant in front of which we parked was unremarkable.

Nevertheless, we entered, met Martin Hett, leader of the French walking federation, and sat down for lunch. Willi took the lead in ordering and while we awaited the meal, we began a tri-lingual conversation.

Willi spoke German as a first language but was mercifully fluent in English and in French. Monsieur Hett added fluency in German to his native French. I stumbled along with a smattering of German but most of the conversation landed linguistically in English.

As we started the discussion, the waiter began to attend to our table. Nothing stood out about the physical condition of the restaurant, but the waiter behaved as though we were in a 3-star Michelin dining room. He was dressed formally in black and white, and my first clue that this was not to be a “food is fuel” experience came as he proudly approached the table balancing a platter elevated elegantly upon his upturned palm. Impressed with the presentation, I was surprised and a bit amused to realize that the sole objective of his formal and somewhat somber visit was the delivery of a pair of salt and pepper shakers.

The conversation progressed nicely. Monsieur Hett was receptive to our plans. What became the focus of the experience for me, however, was the meal. Never having dined in a truly French restaurant, everything was new and intriguing.

The food seemed choreographed to arrive at the right time and in the right relationship to what had preceded and what was to follow. Portions were very small, but I discovered that this too was by design. The flavor of each bite was both powerful and seductive. Larger portions would have been pointless. Each bite was perfect. More would have been irrelevant.

Unlike the evening before in the Gasthaus, alcohol was served with equal intentionality, balanced perfectly with the course of food served. The type of wine or aperitif enhanced the taste and impact of each course of the meal. At least four different types of alcohol, in modest proportions, accompanied the food.

Conversation tripped along gaily, and I found myself entering a mild euphoria. This was a different kind of gemütlichkeit, new in my experience. The intersection of intensely delicious food, calibrated with small portions of perfectly complementary alcohol, while mentally engaged in an amiable, tri-lingual conversation resulted in a cultural connection which still sits at the pinnacle of my travel experiences.

To say that the meeting with Monsieur Hett was successful would be an understatement. We laid the foundation for working with the French walking federation that remains active and amiable to this day (our next visit is to Strasbourg in May 2023). The cultural power of cuisine, however, was a more lasting discovery for me.

My lifestyle priorities were not necessarily altered by the French dining experience with Willi and Monsieur Hett; I still would not often choose to invest what is necessary to have such an amazing experience. But now I better understand why some people do; and I realize there is a time and place for such delicious extravagance.